Today’s post is an interview with Returned Peace Corps Volunteer John (“Sione” in Tongan) O’Malley, who served in Ha’apai from 2009 to 2012. John is now wrapping up his service in Liberia where he works as a Peace Corps Volunteer Leader, but he’s generously taken some time to answer questions about his time in Ha’apai, volunteer life, spear fishing and travel.

Today’s post is an interview with Returned Peace Corps Volunteer John (“Sione” in Tongan) O’Malley, who served in Ha’apai from 2009 to 2012. John is now wrapping up his service in Liberia where he works as a Peace Corps Volunteer Leader, but he’s generously taken some time to answer questions about his time in Ha’apai, volunteer life, spear fishing and travel.

Name: John O’Malley

Place of Origin/Residence: Chicago, Illinois

Any contact info you wish to share:

Feel free to peak at my personal travel blog, JohnOutsideTheLines.Blogspot.com. Active since early 2009, it logs my adventures in Eastern Europe, Tonga, and Liberia.

Email: JJOMalley.3@gmail.com

Current Location:

Liberia, as a Peace Corps Response Volunteer.

Peace Corps Service Location:

Pangai, Ha’apai, Tonga

Peace Corps Time-Frame:

2009-2012

What was your background (college, work, etc.,) before you joined the Peace Corps?

I earned a double major B.A. in History and Biology from Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington, Illinois.

Were you placed in a location and/or field you had indicated an interest in? If not, what were you thoughts on that?

I was anticipating placement into health, agriculture, or community development, thinking it would be a good match for my science skills and my lifelong involvement with the Boys Scouts. Instead I received an invitation to teach in Tongan secondary schools, but I was not disappointed, being happy to serve in any way that I could. I knew all along that teaching was not going to become my career or my life passion, so I was thankful to be able to pursue rewarding health-related secondary projects during my service

What was it like when you first arrived in your new country? Did you think you would enjoy it?

We had only been a few days in country when Peace Corps flew all of us trainees to Ha’apai, the quietest, least developed, and arguably most beautiful of the Tonga’s main island groups. We young, impressionable, naïve Americans would spend the next two and half months living with homestay families and learning about Tongan language and culture. I was so excited. Throw it at me. I can handle it.

Our new families met us at the airport and drove us immediately to our new homes. My mother sat me on a woven mat on her porch to introduce me to my new sisters and to begin her mission of plumping me up with boiled fish and cassava. My large, muscular, and serious father appeared with a kitchen knife and sat solemnly on a stool above, slapping the flat of the knife on his palm. “You better watch yourself in my house,” his mannerisms communicated. This was going to be an uncomfortable few months.

But I couldn’t have been more wrong about him or about the other burly Tongan men. They were the most generous and caring people I had ever met. They treated me like an honored family member and made me feel safe, comfortable, and loved. I remember the first lobster they fed me, when I couldn’t seem to crack open the legs with my teeth. My father cracked them for me, extracting the meat from his own mouth and passing it back like I was a baby bird. The serious policeman demeanor was a thin façade.

I knew these were going to be two great years.

What was your assignment while there?

I was an English, general science, and biology teacher. I taught at the island group’s smallest high school. My typical class sizes were between twelve and thirty students, and the small faculty lived like me on or near the school compound, encouraging me to become close with the whole school community.

The school was austere by American standards. The library had a poor selection of mostly old books; the school computers lacked anti-virus software and had a lifespan of maybe a year; we made classrooms out of porches and teachers lounge out of a closet; we lacked printers and scanners and prayed for the photocopier toner to last as long as possible.

Despite all the challenges, however, the morale at school was high and it was a positive place to work.

Did you engage in a secondary project? If so, what?

Outside of my primary mission as a secondary school teacher, I was also a community health promoter. In conjunction with the Tonga Red Cross, I facilitated sexual health education classes in two area high schools.

I assisted with the national weekly elementary school tooth brushing campaign, lead after school aerobics classes, promoted Red Cross activities, responded as part a post-cyclone Red Cross relief team, and managed the Ha’apai Healthy Eating and Oral Health Peace Corps Partnership Program (PCPP) grant.

The PCPP grant was my grand final project. It financed the printing of hundreds of health promotion posters, pamphlets, and oral hygiene children’s books, and the conduction of health presentations by doctors, nurses, dental therapists, and family planners in 23 villages on 23 islands.

My health work was often more satisfying than my school teaching because it received more appreciative feedback. Young students were ecstatic to see me come help with brushing lessons, and high schoolers confided in me to give them sexual health advice that would have been inappropriate to solicit from community elders. Beaching a boat full of health professionals onto an island of fifty rarely visited Tongans is exhilarating.

Were you posted in a remote or urban setting? What challenges or rewards have you experienced because of this?

Pangai is the capital town of the Ha’apai Island Group, but it is still a small town. One main road runs through it and vehicle traffic is minimal. There are several small “Chinese Stores” selling low-quality basic goods. There is a nearby hospital, four high schools, a small restaurant, a police station, a court house, small shops, two cellular towers, many churches, and a short wharf for docking the occasional resupply ship. The tallest building is only three stories high.

Pangai didn’t feel urban, but it also had everything we needed. Volunteers on other outer islands wanted for luxury goods like frozen chicken and ultra-high pasteurized milk. While there were many times I wished I could have had a Coke Zero or a decent hamburger, Pangai felt pretty Posh Corps.

What was the living condition for the people there?

The average Ha’apaian home was constructed of wood or brick with a corrugated metal roof. Wooden homes were usually raised on stilts about a meter off the ground, and the pigs usually lived below. Most homes had electricity and either plastic or cement rainwater collection tanks. Nicer homes had well-constructed furniture, couches, appliances, and maybe a television. More basic homes would lack the furniture and appliances, but neighbors are so communal that they all shared their resources. My homestay family had the nicest house in the village, so they often had village kids over to watch movies.

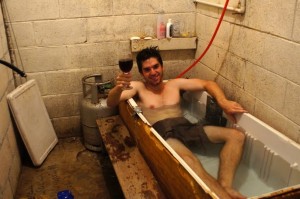

Bathing was by bucket. Cooking was by open fire or underground oven and used coconut husks as fuel.

Those Ha’apaians not working for the government or the few businesses in Pangai were most often fisherman and agriculturalists. Fisherman feed their own families, sell a little locally, and sell most to Tongatapu, Tonga’s largest island. Substantial inflows of cash came from remittances from family members in New Zealand, Australia, and America.

After graduating from high school, many of my students would go to follow their parents into the church, the fields, or the sea. The more educated would leave Ha’apai and head for the work or education opportunities on the main island or seek tertiary education abroad.

What are the health concerns, if any?

As a visiting American, there were glaring health concerns in Ha’apai; obesity, diabetes, and heart disease were high. Diet was high in salt, sugar, and saturated fat. Women tended not to exercise. The local hospital did not have nearly the capabilities of a suburban American hospital, making us nervous about experiencing any major accidents.

The Ha’apaians, however, didn’t see these health concerns as we Americans did. They seemed mostly happy with their lives and their health and their amount of exercise. They had a Christian acceptance of untimely death as being God’s will.

Sexual health received more recognition as a health concern, but only from students, some health workers, and a cadre of adults interested in learning about a subject that was culturally prohibited from being discussed publicly. Ha’apaians grew up without formal sex education and without having experts or materials to privately consult about it. Conducting sexual education classes at the high school and having Tongans excitedly join them was one of the most rewarding accomplishments of my service.

What was the greatest need, based on your observation?

The obvious American answers are health and business development. Having lived with Ha’apaians for two years, however, I might now disagree. If they are happy with their own health, and if store owners would rather invest more in helping their neighbors than in reinvesting their businesses, then perhaps aid should be refocused into more emergent concerns like coastal erosion and waste disposal. At the rate the shores are eroding, there may not be much of Ha’apai left in a hundred years.

Is there a particular experience that stands out in your mind related to your volunteer work at your post?

At the conclusion of my service, my school gave me a going away feast as part of the school graduation ceremony. They sat me at a decorated head table bursting with roasted pig, fish, lobster, chicken, noodles, root crops, soda, chips, and candy. Community elders, teachers, administrators, and ministers flattered me with speeches and prayers and the formalities while sixty students and parents watched and nodded. I responded with my own humorous yet endearing Tongan-language thank-you speech, concluding what Tongans would call a perfect going-away party.

The ceremony was touching, and delicious, but it was also too formal and impersonal for me to accept as my last big meal with my friends. Having done goodbye the formal Tongan way, I would now do it the American barbecue way. Days later, I invited by closest friends and neighbors to roast a pig with me. We bought, killed, and cooked it together, and threw some barbecue chicken on the grill for good measure. We listened to music, drank sodas, and joked around while the food cooked in front of us.

When the food was all ready we ate together in the grass on paper plates. It threw them not to arrange seating by social hierarchy, not to dignify me with my own chair and table, and not to give grandiose speeches. We had was a cozy, casual, egalitarian barbecue, and, after it was all over, my principal and close friend admitted, “Hey, that was kind of fun. We just sat there all together… in the grass!”

With my last week at site, Ha’apai was able to share their ceremonial culture with me, and I was able to share my casual culture with Ha’apai. We all got what we wanted, and we all had a good time doing it.

What was your housing like? Did you live alone or with a family? What challenges and rewards have you experienced from this?

I lived well by global Peace Corps standards. I lived alone in a solidly constructed house on the school compound and shared a wall with the home economics room. I had twenty-four hours of electricity and running water. I owned a refrigerator, an oven, a stove, and a computer. I lived comfortably and safely and rarely locked my door while I was away.

Living at the school increased my accessibility to students interested in help and drew me into the community. The faculty lived close by and came regularly to visit me. I felt so loved.

Being so exposed could also be trying. I liked being alone sometimes, but Ha’apaians assumed that to be alone was to be unhappy. They were determined to cheer me up with constant company. Students and neighbors would often borrow items from me and fail to return them, but the idea of borrowing was very different in Tongan culture and items weren’t expected to return. They were unselfish with their possessions; I was the opposite.

What did your diet typically consist of?

My chief proteins came from store-bought American chicken and from fresh fish I would catch myself. When I was lazy I would buy canned fish, a staple of the Tongan diet. My starches were pasta, rice, and the myriad available root crops.

Vegetables were more difficult to find, and before my tomato garden flourished in my second year, I was limited to onions, peppers, and the seasonal eggplant and carrots. Watermelons, papaya, mangoes, and pineapple were seasonally delightful fruits.

The best meal of week came every Sunday after church. I would go with my school neighbors to the hour and a half long service and then retire home to enjoy their underground oven cooked Lu (onions, coconut milk, and protein, wrapped in many layers of Lu leaves and an outer covering of banana leaves). Served with a size of breadfruit or cassava, and drizzled with imported Sriracha sauce, it was delectable.

I snacked on peanuts, crackers, and the occasional bag of chips. For my first year there was an ice cream shack in town that alleviated hot tropical afternoons.

What was a typical day for you?

With my classes scheduled sporadically throughout the day I found myself filling the gaps with grading, lesson planning, writing and reading.

After school I could go fishing, meet fellow Volunteers, work on my house, study for the Foreign Service exam, work on my garden, go swimming, lift weights or bike ride. More construction work and studying the first year; more gardening and exercising the second.

Sundays were very Tongan: church, food, and multiple naps.

The best part of every day began with a cast of orange over my living room wall. That was my signal to walk two hundred feet out my front door to the fallen coconut tree resting in the sand, to pet my dog, to wiggle my feet in the water, and to watch the sun fall into the ocean somewhere between ‘Uoleva island and our pair of Volcanoes. When the sun disappeared it was time to make dinner.

What was the hardest thing about your PC experience?

My Ha’apaian friends, neighbors, students, and coworkers were happy, helpful, generous, and respectful, and it helped make for a great experience. I could walk freely around the island anywhere and at any time. I could trust complete strangers. I could leave doors unlocked. If I ever found myself hungry, I could walk to a random house and ask to eat with them.

While Ha’apaian attitudes were the best part of my Peace Corps service, it could also be frustrating. There is an expectation of mutual generosity, so anything you own should be made available to everyone. Americans with strong delicate, expensive electronics and strong opinions about private property, however, usually struggle with lending. In the end, I learned how to be a more generous, less materialistic person, and how to set appropriate boundaries with neighbors, but it was a difficult lesson to learn.

Ha’apaian happiness could also be frustrating. My fellow islanders didn’t appear poor, needy, or underdeveloped. Their crops were minimally intensive, there were high rates of remittances, and they didn’t need expensive things. They seemed happier overall than most Americans I knew. Since life was simple in Ha’apai, and life’s necessities were provided, why, then did they need to have health-related secondary projects, to conduct teaching workshops, and to build gardens? While I was a task-oriented, hard-working college graduate looking to impact great changes on the island, my best Ha’apaian friends would rather I sit with them and drink Kava and tell stories.

What was the most rewarding thing?

See previous answer.

What was the area like when you first arrived? Have you noticed any changes since that time?

Pangai, the largest town in Ha’apai, did not change much over my two years. It garnered a fourth “Chinese Store” that did not much add to the variety of goods available besides their small wine selection. A two-pump gas station went in. Some trees and homes had fallen from the two cyclones that attacked the island. Except for beach erosion, Pangai was the same sleepy town when I left that it was when I arrived.

What were your hobbies or activities you engaged in during your free time?

I partook in the standard Peace Corps Volunteer leisure activities like reading, sleeping, enjoying my neighbors, bike riding, playing with my dog, and watching hard drives of American television shows. I also dedicated many hours each week to blogging.

I was lucky to have several outstanding Volunteers share my island with me or live nearby. Our proximity allowed us to throw group dinners and campfires, to walk and bike together, and to grow very close to each other. We helped each other with projects, supported each other in hard times. I owe as much to Juleigh, Todd, and Blair for making my experience extraordinary as I do to my Tongan friends.

My favorite way to spend an afternoon was to grab my mask, fin, snorkel, wetsuit, weight-belt, and spear gun, and to bike ten minutes down to where the reefs teemed with fish. I would spend hours hunting for the next week’s protein source in what was also the most fun and visually spectacular form of exercise I’ve ever experienced.

What was your favorite place to go?

Ha’apai was conveniently located between the country’s two other main island groups, Tongatapu and Vava’u, so when Tonga PCVs wanted to meet up, they often came to us. Whenever anyone came to visit, we’d take them to ‘Uoleva Island.

‘Uoleva was the next island south of our main island, and it was inhabited by probably only five permanent people – the managers of the island’s three minimalist “resorts.” The beaches were pristine and the reefs were bountiful.

At low tide we could walk there across the reef, and at other times we could sail or motor there. We’d pitch tents, acquire young coconuts for drinking, build fires, and enjoy a simple weekend likely to beat anything you’ll find in an Apple Vacations catalogue. On ‘Uoleva I spent my first ever Christmas away from home. I wasn’t homesick.

What other places did you visit while there? What were your favorites?

Ha’apai is a vast and sparsely populated island group. I was lucky to be able to visit almost every one of Ha’apai’s inhabited islands while on my week-long outer island health promotion tour as part of my Ha’apai Healthy Eating and Oral Health Peace Corps Partnership Program grant. The outer Ha’apaians were appreciative of the opportunity for medical care, and they showed me great generosity. The environment was beautiful, but by week’s end I was exhausted.

A couple times a year I was able to visit Tonga’s other main island groups of Vava’u and Tongatapu, so I was able to see and keep up with all of the Volunteers from my training group. Ha’apai was for beaches and snorkeling and relaxation. Vava’u was for sailing trips and parties. Tongatapu was for restaurants, shopping, and getting stuff accomplished while at the main office.

Tonga does not have many international connections, but I was able to venture on holiday to New Zealand and Fiji. New Zealand is bucolic, entertaining, and deliciously rejuvenating spa. It helps remind you of home while continuing to satisfy your travel bug. I can’t wait to go back. Fiji is a much larger, more developed and less expensive Tonga. Its tourism infrastructure satisfies cravings for resorts and luxury and McDonald’s in ways that Tonga can’t.

If visitors came to your location, what highlights would you recommend?

Visitors to Ha’apai should stay and eat at Matafonua resort on the northern tip of Foa Island. Join the proprietors on any trips or excursions they may have going (be it snorkeling, boating, SCUBA diving, or arranging a trip to a Tongan village). Spend just a few days on ‘Uoleva island if you truly want to get away to a beautiful and nearly deserted island, but not if you like your luxuries. Connect with Peace Corps Volunteers to have a more cultural experience.

What would you recommend visitors bring in terms of clothing and supplies?

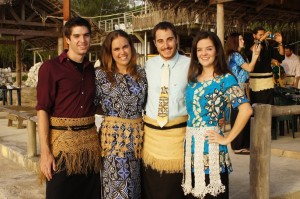

More important than any packing list are some guidelines for dress. Ha’apai is a more traditional island than most of Tongatapu or Vava’u, and dress should be conservative: don’t show much shoulder or legs above the knee. A male tourist in Ha’apai should acquire a ta’ovala and tupenu as soon as possible after arriving in country. A tupenu is the wrap-skirt that is standard attire for Tongan males. A ta’ovala is the reed mat that wraps over the skirt. Women should wear skirts below their kiekie, thin belts with dangling ornaments.

Tourists don’t need to dress so formally, but it makes Tongans so happy to see you integrating. They are more likely to help you and your experience will be more satisfying.

What would you recommend volunteers bring?

I recommend bringing spices, sauces, loose teas, and feel-good foods for those frustrating days. Seed packets would help start the garden you’ll need during the really hot and dry season when market vegetables are rare.

I’d also recommend luxury goods like a computer, camera, and portable rechargeable speakers. Computers are productive machines and can play those movies Volunteers are always passing around. Cameras can capture what will probably be two most photogenic years of your life.

Also, a quality spear gun, if somehow you know you’ll be assigned to Ha’apai. Much less useful in Vava’u or Tongatapu.

Do you have a favorite restaurant? If so, what, where, etc.?

If someone hopped on my bike and rode an hour and a half north – across the landbridge into Foa Island, past five villages, and to where the road ended at a narrow point of sandy beach – they would arrive at Matafonua resort. A property of newly constructed comfortable cabins and restaurant run by a hilariously affable couple, Matafonua has a view of the ocean you’ll remember forever. It was also the best food you’ll find without a plane ride.

If you are a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer (“RPCV”), what are you doing presently?

As I write this, I am two months away from finishing my year and half long assignment as the Peace Corps Volunteer Leader in Liberia. I came here almost immediately after finishing my service in Tonga and I’m so glad I did. Liberia is such a different country. I went from a safe and placid middle-income tropical archipelago to a struggling post-conflict zone that is the poorest country that Peace Corps serves. Liberia has helped me appreciate the calm, the safety, and the infrastructure in Tonga.

If you are a RPCV, did you have difficulty re-adjusting to life post-PC? Please explain as much as you feel comfortable.

In my four years of Peace Corps service, I have been Stateside on holiday four times. The emotional import of coming home wanes a little each time, but never is there much culture shock. My friends and family welcome me back every time as though little has changed. The jubilation from those first visits to grocery stores, movie theaters, and shopping malls quickly fades, and old routine sets in. What doesn’t revert, however, are my new-found appreciations for life’s luxuries, like hot showers, sourdough pretzels, and craft beer.

Overall, how would you summarize your PC experience?

I arrived in Ha’apai expecting to meet poor, struggling denizens desperate for development help. I expected to spend next two years overworked helping fill deficits in the Tongan education system and using my free time to help with a multitude of secondary projects.

In actuality, I did work hard at school and did have meaningful secondary projects, but Tongans didn’t express the need and demand the help that I expected. They were a satisfied people happy just that I had come to live with them for two years. They’d rather I sit to speak Tongan with them, go fishing, drink their kava, eat their food, and watch their rugby teams than to struggle with secondary projects.

It was a frustrating psychological adjustment, but I embraced it, and in the end, I feel that I got more out of my service than they did. My Tongan and American friends taught me the values of generosity and the fallacy of materialism, and the friendships I made there will last my lifetime.

I love your website. tongatime.com would probably one of the best site I’ve read in a write. Keep up the good work.

SEMISI SAAFI

100% Tongan

Thanks, Semisi! Having Tonga as the inspiration certainly helps. :)

Hi Jesse,

One of the best website/blogs I’ve read. This entry, in particular, was wonderful. I found myself smiling several times. I will be in Tonga Group 79 come Sept 1st. Reading all this has really helped put me at ease. Thank you!

Hey Lana,

Thanks for visiting and congratulations on your Tonga assignment! Will you be stationed in Nuku’alofa? I’m excited for you and I’m sure you’ll love your experience. Don’t forget to bring your snorkel gear as Tonga has the clearest, most gorgeous water … EVER!

Toki sio,

Jesse